Начало. 02. Основатели и учителя

![]()

李时珍 (李時珍) Lǐ Shízhēn Ли Шичжэнь | Dong Bi (Tung-pi) (東璧 Dōng Bì

![]()

Википедия:

Ли Шичжэнь (кит. трад. 李時珍, упр. 李时珍, пиньинь: Lǐ Shízhēn; 1518—1593) или Dong Bi (东璧) — крупный китайский врач и фармаколог XVI века.

Ли Шичжэнь известен своим монументальным трудом «Бэньцао ганму» («Основы фармакологии»), в котором за 27 лет работы обобщил опыт, накопленный китайскими врачами за предшествующие века.

В 52 томах своего произведения он описал 1892 лекарственных средства, главным образом растительного происхождения. Он дал не только описания растений, но и способы, время сбора, методы приготовления и употребления растений для лечения.

Ли Шичжэнь изучал методы лечения народных врачей и вел усиленную просветительскую борьбу, в частности, против распространявшихся в традиционном Китае «пилюль вечной жизни», составленных из ртути и других ядовитых соединений.

![]()

Wikipedia:

Li Shizhen

Herbologist and Acupuncturist

Born 1518 – Died 1593 (aged 74–75)

Names:

Traditional Chinese: 李時珍

Simplified Chinese: 李时珍

Pinyin: Lǐ Shízhēn

Wade–Giles: Li3 Shih2-chen1

This is a Chinese name; the family name is Li.

Li Shizhen (Li Shih-chen; simplified Chinese: 李时珍; traditional Chinese: 李時珍; pinyin: Lǐ Shízhēn; Wade–Giles: Li3 Shih2-chen1, July 3, 1518 – 1593), courtesy name Dongbi (Tung-pi; Chinese: 東璧), was a Han Chinese polymath, medical doctor, scientist, pharmacologist, herbalist and acupuncturist of the Ming dynasty. His major contribution to clinical medicine was his 27-year work, which is found in his scientific book Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu). He is also considered to be the greatest scientific naturalist of China, and developed many innovative methods for the proper classification of herb components and medications to be used for treating diseases.

The Bencao Gangmu is a medical text with 1,892 entries, each entry with its own name called a gang. The mu in the title refers to the synonyms of each name.[1] The book has details about more than 1,800 drugs (Chinese Medicine), including 1,100 illustrations and 11,000 prescriptions. It also described the type, form, flavor, nature and application in disease treatments of 1,094 herbs. His Compendium of Materia Medica has been translated into many different languages, and remains as the premier reference work for herbal medicine. His treatise included various related subjects such as botany, zoology, mineralogy, and metallurgy. The book was reprinted frequently and five of the original editions still exist.[2]

Biography

A statue of Li Shizhen found at Peking University Health Science Center.

In addition to Compendium of Materia Medica, Li wrote eleven other books,[3] including Binhu Maixue (Pin-hu Mai-hsueh; Chinese: 《瀕湖脈學》; “A Study of the Pulse”) and Qijing Bamai Kao (Chi-ching Pa-mai Kao; Chinese: 《奇經八脈考》; “An Examination of the Eight Extra Meridians”).[4] He lived during the Ming Dynasty and was influenced by the Neo-Confucian beliefs of the time. He was born in what is today Qizhou,[5] Qichun County, Hubei in July 3, 1518 AD and died 75 years later, in 1593.[3]

Li’s grandfather had been a doctor who traveled the countryside and was considered relatively low on the social scale of the time. His father was a traditional physician and scholar who had written several influential books. He tried to move up in society and encouraged his son to seek a government position. Li took the national civil service exam three times, but after failing each one, he turned to medicine. At 78, his father took him on as an apprentice. When he was 38, and a practicing physician, he cured the son of the Prince of Chu and was invited to be an official there. A few years after, he got a government position as assistant president at the Imperial Medical Institute in Beijing. However, even though he had climbed up the social ladder, as his father had originally wanted, he left a year later to return to being a doctor.[3]

In his government position, Li was able to read many rare medical books; he also saw the disorder, mistakes, and conflicting information that were serious problems in most medical publications of the time and soon began the book Compendium of Materia Medica to compile correct information with a logical system of organization. A small part was based on another book which had been written several hundred years earlier, Jingshi Zhenglei Beiji Bencao (Ching-hsih Cheng-lei Pei-chi Pen-tsao; “Classified Materia Medica for Emergencies”) – which, unlike many other books, had formulas and recipes for most of the entries. In the writing of the Compendium of Materia Medica, he travelled extensively, gaining first-hand experience with many herbs and local remedies and consulted over 800 books – nearly every medical book in print at the time.[3]

Altogether, the writing of Compendium of Materia Medica took 27 years, which included three revisions. Ironically, writing the book allegedly took a considerable toll on his health.[3] It was rumored that he stayed indoors for ten consecutive years during the writing of the Compendium of Materia Medica.[6] After he had completed it, a friend “reported that Li was emaciated.”[3]

Li died before the book was officially published, and the current emperor paid it little regard.[3] However, it remained one of the most important materia medica of China.

Compendium of Materia Medica

Compendium of Materia Medica is a pharmaceutical text written by Li Shizhen during the Ming Dynasty of China.

Compendium of Materia Medica was a massive literary undertaking. Li’s bibliography included nearly 900 books. Because of its size, it was not easy to use, though it was organized much more clearly than others that had come before,[3] which had classified herbs only according to strength. He broke them down to animal, mineral, and plant and divided those categories by their source. Dr. S. Y. Tan[6] says: “his plants were classified according to the habitat, such as aquatic or rock origins, or by special characteristics, e.g. all sweet-smelling plants were grouped together.”[6]

Li had exemplary recording techniques. Seeking to fix the errors of previous works, the medicinal plants and substances in the Compendium of Materia Medica were clearly organized and categorized. With every entry, he included:

- “Information concerning a previously false classification;

- Information on secondary names, including the sources of the names;

- Collected explanations, commentaries and quotes in chronological order, including origin of the material, appearance, time of collection, medicinally useful parts, similarities with other medicinal materials;

- Information concerning the preparation of the material;

- Explanation of doubtful points;

- Correction of mistakes;

- Taste and nature;

- Enumeration of main indications;

- Explanation of the effects; and

- Enumeration of prescriptions in which the material is used, including form and dosage of the prescriptions.”[3]

- Compendium of Materia Medica contained nearly 1,900 substances, which included 374 that had not appeared in other works. Not only did it list and describe the substances, but it also included prescriptions for use – about 11,000 – 8,000 of which were not well known.[3] The Compendium of Materia Medica also had 1160 illustrated drawings to aid the text.[4]

In addition to writing Compendium of Materia Medica, Li was one of the first to recognize gallstones, use ice to bring down a fever, and to use steam and fumigants to prevent the spread of infection. Li also emphasized preventative medicine.[6] He said that “‘To cure disease is like waiting until one is thirsty before digging a well…’” and listed over 500 treatments to maintain good health and strengthen the body, 50 of which he invented himself.[4]

Compendium of Materia Medica still has scientific, medical, and historical significance today. A plant or substance’s inclusion in the Compendium of Materia Medica is a sign of posterity. Medical clinics and manufacturers use his name and image on their logos and products and there was even a movie made about his life in 1956. His image can be found at almost every traditional medical college in China, as well as many books on Chinese medicine and there is even a Li Shizhen award for “doctors and researchers who have made valuable contributions to traditional Chinese medicine.”[3]

While only six copies of the original edition remain – One in the US Library of Congress, two in China, and three in Japan (a seventh copy in Berlin was destroyed during World War II)[6] – several new editions and numerous translations have been made throughout the centuries, and it was not replaced as the pharmaceutical materia medica of China until 1959: over 400 years after its first publication.[3]

Notes:

1. Zohara Yaniv; Uriel Bachrach (2005). Handbook Of Medicinal Plants . Psychology Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-56022-995-7.

2. Original text from Li Shizhen , licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License.

3. Dharmananda, Subhuti. “Li Shizhen: Scholar Worthy of Emulation.” Institute for Traditional Medicine. Institute for Traditional Medicine. 25 Apr. 2006 <http://www.itmonline.org/arts/lishizhen.htm >.

4. “The Herbal Tradition.” PlanetHerbs.Com. 2005. 24 Apr. 2006 <http://www.planetherbs.com/articles/herbhist.html >.

5. Panyu Tiger: Li Shizhen 李時珍

6. Tan, S Y. “Medicine in Stamps — Li Shih-Chen (1518-1593) — Herbalist of Renown.” Singapore Medical Association. 2003. University of Hawaii. 24 Apr. 2006 <http://www.sma.org.sg/smj/4407/4407ms1.pdf >.

![]()

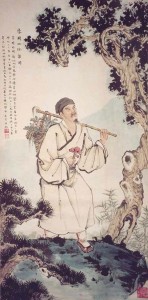

Ancient Pharmaceutical Wisdom. Li Shizhen: Icon of Chinese medicine

The painting is by artist Zhang Cuiying.

Li Shizhen (1518-1593 A.D.), also named Li Dong Bi, was from Chai State of the Ming Dynasty or today’s Chai Cun, Hubei Province of China. Li Shizhen was the author of Compendium of Materia Medica (or Ben Cao Gang Mu in Chinese). [1] It took Li Shizhen 30 years, 800 medical books, and three revisions to finish Compendium of Materia Medica. The book has 52 volumes and is still a very popular book in print. Li Shizhen was also the author of Seven Channels and Eight Pulses (or Qi Jing Ba Mai in Chinese) and Lake Bin Pulse Diagnosis (or Bin Hu Mai.) Li Shizhen is one of the best known Chinese pharmacists in ancient times.

Li Shizhen’s research methods were to “study medical reference books intensively” and “consult uneducated people who live close to nature.” To “study medical reference books intensively” refers to the fact that Li Shizhen read over 800 medical reference books. “Consult uneducated people who live close to nature” refers to the fact that Li Shizhen learned the medicinal properties of herbs from knowledgeable herb growers, firewood choppers, farmers and hunters. Li Shizhen roamed over mountains and ridges for thousands of miles to conduct field studies on medicinal herbs. He never felt ashamed of asking and learning from the less educated people about medicine. After 30 years of reading and field study, Li Shizhen finally finished the first draft of Compendium of Materia Medica in 1578.

Li Shizhen wrote in his Seven Channels and Eight Pulses: “The inner passageways of a human body can only be observed by those who are capable of introspection.” In other words, Li Shizhen said only those who have their Third Eye open can see within a human body to examine its inner channels and pulses.

In this portrait, Li Shizhen, the Shen Nong of the Ming Dynasty is walking in nature wearing a pair of straw sandals, while carrying an herb hoe and herb basket filled with herbs he had collected. [2]

Notes:

[1] Compendium of Materia Medica is a pharmaceutical text written by Li Shizhen during the Ming Dynasty (1386 – 1644 A.D.), which lists all the animals, vegetables and other objects believed to contain medicinal properties in traditional Chinese Medicine.

[2] Shen Nong was a God in ancient Chinese mythology who led people to travel thousands of miles to look for crops and herbs. He taught humankind agricultural knowledge and skills. He tasted hundreds of herbs to learn their medical properties and thus created Chinese herbal medicine.

![]()

Hujian Chinese:

Compendium of Materia Medica 《本草纲目》

The Bencao gangmu 本草纲目 “Guidelines and details of materia medica” is China’s most important traditional book on pharmaceuticals. It is 52 juan”scrolls” long and was written by the famous Ming period 明 (1368-1644) herbologist Li Shizhen (1518-1593), courtesy name Li Dongbi 李东壁, stylePinhu shanren 濒湖山人. He came from Qizhou 蕲州 (modern Qichun 蕲春, Hubei), and hailed from a family of physicians. His father Li Yanwen 李言闻, also called Li Yuechi 李月池, was a medical secretary in the Imperial Academy of Medicine (taiyi limu 太医吏目) and had written the books Sizhen faming 四珍发明, Aiyezhuan 艾叶传 and Douzhen zhengzhi 痘疹证治. Li Shizhen himself was an enganged student of his own father but did not have the ambition to achieve a career in the civil service. He nevertheless became a physician at the court of Zhu Yingxian 朱英{火+佥}, the Prince of Chu 楚, and later even administrative assistant in the Imperial Academy of Medicine (taiyi yuanpan 太医院判).

Li was a well-read person and had studied many kinds of books, from the obligatory Confucian Classics and the histories to the books of the masters and philophers, and, of course, specialized books on medicine and herbology. He therefore possessed an excellent overview of all statements on material medica in various types of literature. Yet Li Shizhen also gathered information from peasants, fishermen, travelers and craftsmen about drugs, their preparation and their effects, and was, as a physician, also experienced in the practical use of materia medica in clinical medicine. As a herb collector he was able to correct many errors and uncertainties in older books, for instance, the fact that the herb penglei 蓬虆 was in fact five different types of rubus. Old writings included many wrong statements about pharmaceuticals and it was therefore necessary to correct these errors and to add new, useful information. It was further necessary to add drugs that had not been known in earlier times. Li Shizhen took this task very seriously, visited experienced doctors and collected all kinds of information he was able to obtain. He had also prepared pictures of all pharmaceuticals that were later included in his book.

Li Shizhen evaluated more than 800 different sources, among these 276 medical books, and compiled his large book on material medica according to the pattern of the Song period 宋 (960-1279) pharmacopoeia Zhenglei bencao 类证本草. The compilation process consumed almost three decades, and the manuscript was revised three times. The book was finished in 1578 and the publication process began immediately, but Li Shizhen died before its completion.

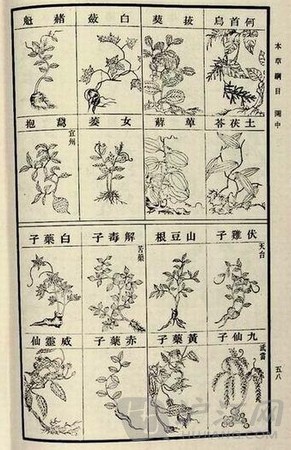

The book is divided into 16 large classes of pharmaceuticals, according to their nature, that are divided into 62 sub-classes. Herbs, for instance, are divided into mountain herbs (shancao 山草), fragrant herbs (fangcao 芳草), marshland herbs (xicao隰草), creeping herbs (mancao 蔓草), poisonous herbs (ducao 毒草), aquatic herbs (shuicao 水草), stone herbs (shicao 石草), moss (taicao 苔类) and miscellaneous herbs (zacao 杂草). Inside the sub-classes the materia medica are arranged according from the smaller to the larger, the less valuable to the expensive drugs, and the simple to the complex.

The Bencao gangmu describes 1,892 different pharmaceutical objects, which is 374 more than in earlier pharmacopoeias. These additional herbs and objects mainly originate in regions that were formerly not part of the Chinese empire, especially the northwest and the southwest. Some drugs also come from abroad, like grapes (putao 葡萄), carrots (hu luobo 胡萝卜), pumpkins (nangua 南瓜), yam (ganshu 甘薯), Panax pseudo-ginseng (sanxi 三七), yasmin (moli 茉莉), tulips (yujinxiang 郁金香) or camphor (zhangnao 樟脑). The Zhenglei bencao provided a number of 1,479 drugs, and 39 drugs were included in sources from the Jin empire 金 (1115-1234) and the Yuan period 元 (1279-1368). The book is enriched with 1,109 illustrations of minerals, plants and other pharmaceutical objects. These illustrations are in most editions of the Bencao gangmu positioned at the beginning of the book. The illustrations were compiled by Li Shizhen’s son Li Jianzhong 李建中 and painted by Li Jianyuan 李建元 and Li Jianmu 李建木. The quality of the paintings it not very superior, but they suffice to identify the plants.

The Bencao gangmu includes 11,096 recipes and treatment methods for various diseases. The large amount of drugs covered in the Bencao gangmu is owed to the principle of Chen Cangqi’s 陈藏器 Bencao shiyi 本草拾遗 “Collected addenda to the pharmacopoeias” not to leave out any single information, but also to the Neo-Confucian attempt at investigating all things (ge wu 格物), like the Song and Yuan period physicians Zhang Yuansu 张元素 and Li Dongyuan 李东垣 had already done.

1,094 drugs are made of plants, which is more than half of all materia medica dealt with in the Bencao gangmu, and shows that “roots and herbs” (bencao 本草) were in fact the most important tools of an apothecary in ancient China. 276 drugs are made of minerals, and 444 out of parts of animals.

The pharmaceuticals are arranged according to their physical nature, beginning with anorganic substances, namely water (shui 水), fire (huo 火), earth (tu 土) and metals and minerals (jin shi 金石), which reflect four of the elements of the Five Processes 五行. The fifth element, wood (mu 木), is represented in the next part, divided into herbal plants (cao 草), grains (gu 谷), vegetables (cai 菜), fruits (guo 果), and trees (mu 木). This section is followed by six groups of moving creatures, namely worms, amphibia and reptiles (chong 虫), fishes (lin 鳞), animals with a shell, including turles (jie 介), birds (qin 禽), beasts (shou 兽), and man (ren 人). Another anorganic section is that of textiles and tools (fuqi 服器).

The first two juan include an introduction (xuli 序例) in which the seven basic methods (qi fang 七方) are described, the ten preparation methods (shi ji 十剂), the concepts of energy (qi 气), taste (wei 味), Yin and Yang 阴阳, rising and falling (shengjiang 升降), floating and submerging (fuchen 浮沉), the outwards phenomena (biaoben 标本) of the inner zang 脏 andfu 腑 organs, as well as the combination of drugs that mutually require each other, catalyse, avoid, “hate”, “contradict” or even “kill” each other. The basic methods of application are described and what restrictions are to be observed. The introduction also explicates the functional quality of drugs that can be divided into “lords” (jun 君), “ministers” (chen 臣), and “assistants and runners” (zuo li 佐使). The introduction also includes an overview over pharmarcopoeias of earlier times and mentions 41 pharmaceutical books.

Juan 3 and 4 enumerate the most important standard pharmaceuticals that heal the 177 most oftenly occurring diseases and are easily to applicate. The main part of the book contains the detailed description of a huge number of pharmaceutical drugs. The description is systematically divided into eight parts, beginning with an analysis of the different names of drugs (shiming 释名), collected explanations (jijie 集解) about the places of origin, the genral appearance and the colleting methods of the drug, discussions of doubts (bianyi 辨疑) and corrections of errors occurring in older texts (zhengwu 正误), preparation methods (xiuzhi 修治), energy and taste (qiwei 气味), healing effects (zhuzhi 主治), and “enlightenments” (faming发明). All these parts quote extensively from older sources and are enriched by Li Shizheng’s own remarks. An appendix chapter for each drug is commented regarding concrete treatment methods (fufang 附方).

Li Shizhen analysed many statements of older texts and found out many errors that he was able to rectify, like the fact thatPolygonatum odoratum (weirui 葳蕤) and Clematis apiifolia (nüwei 女萎) are two different plants, or that nanxing 南星 andhuzhang 虎掌 are the same drug, namely Pinellia temata. He also shifted ginger (jiangsheng 生姜) and Chinese yam (shuyu 薯蓣) from the herbs chapter to the chapter on vegetables, and betel (binlang 槟榔) and longans (longyan 龙眼) from the trees chapter to the fruits chapter. He discerned the proper orchids (lanhua 兰花) and Eupatorium fortunei (lancao 兰草), likewiseLilium lancifolium (juandan 卷丹) and proper lilies (baihe 百合), Polygonatum sibiricum (huangjing 黄精) and Gelsemium elegans (gouwu 钩吻), Calystegia sepium (xuanhua 旋花) and Alpinia japonica (shanjiang 山姜). Li Shizhen also renounced some older statements that were wrong in a pharmacological way. Quicksilver (shuiyin 水银), for instance, was thought to be non-toxic and was therefore consumed in great doses because people thought its consumption would lead to immortality. Ancient Daoist books like the Baopuzi 抱朴子 had an influence on medical treatises like the Mingyi bielu 名医别录 and theBencao shiyi, so that statements about the allegedly healthy application of gold (huangjin 黄金), realgar (As4S4, xionghuang雄黄), orpiment (As4S6, cihuang 雌黄) or cinnabar (HgS, dansha 丹砂) were recorded in pharmaceutical books. He also criticized superstitious beliefs like the theory of fish that grow out of grass seeds, or Cynomorium songaricum (suoyang 锁阳) growing in the earth out of horse sperm. On the other side, Li Shizhen clinged to some of these beliefs, like the theory that flies emerge out of rubbish or the superstitious belief that if a pregant woman does not eat meat, her baby will be born without lips.

The Bencao gangmu has a scientific value that can not be underestimated. It is therefore the most important pharmaceutical book in traditional China. It is a thorough and systematic compendium on Chinese parmacology until the mid-16th century. The book is arranged as guidelines (gang 纲) surrounding “meshes” (mu 目), the drug and its direct description constituting the guidelines, and its specifics corresponding to the “meshes”. Other explanations see the 16 basic categories as “guidelines” and the subcategories of drugs as “meshes”. Similarly, “genera” (like liang 粱 “millet”) can be seen as guidelines, while “species” (like chiliang 赤粱 “red sorghum” and huangliang 黄粱 “yellow sorghum”) are the “meshes”. The description of individual drugs includes the origin of the materia, the place where it grows, lives or can be found, its appearance and collection method, as well as the preparation method of the required drug. Li Shizhen also explains experiences with the drug made by earlier physicians, and his own experiments. The entry of each drug is enriched by an appendix on treatment (fufang 附方), in which Li Shizhen explains 8,161 different recipes and treatment methods.

Li Shizheng’s text is so comprehensive that the Bencao gangmu is not only a pharmaceutical book but can be used for informations on botany, zoology, chemistry and mineralogy. In the field of biology, for instance, Li Shizhen describes many details on lotus. He says that wild lotus has a red flowers, many stalks, but few roots, while the cultivated white lotus has precious roots. The species or kind of hehuan 合欢 has great heads, yeshuhua 野舒荷 opens at day and rolls in the petals at night, while shuilian 睡莲 submerges during the night. The kind of jinlian 金莲 has golden flowers, that of bilian 碧莲 green flowers, and xiulian 绣莲 flowers look like embroideries. In the field of geology or mineralogy he lists the places where petrol (shiyou 石油) is to be found in China, and explains that the local population stores the oil in jars and uses it as a fuel for lamps. The water lever in course terracotta jars can say a lot about the moisture of the air, as he explains, and can eventually predict rainfall. Li Shizhen gives an example to test the identity of chalcantithe (shidan 石胆, today called danfan 胆矾). He also believed that the brain was the organ of the “primordial spirit” (yuanshen zhi fu 元神之府), and not, as traditionally believed, the heart.

Except the Bencao gangmu Li Shizhen has also written a number of other medical books, like Pinhu maixue 濒湖脉学 (shortly called Maixue 脉学), Qijing bamai kao 奇经八脉考, Maijue kaozheng 脉诀考证, Wuzang tulun 五脏图论, Sanjiao kenan 三焦客难,Mingmen kao 命门考, Shiwu bencao 食物本草, Pinhu yi’an 濒湖医案 and Jijianfang 集简方. A biography of Li Shizhen can be found in the official dynastic history Mingshi 明史 (in the chapter of magicians, Fangjizhuan 方伎传), and in Gu Jingxing’s 顾景星 collected writings Baimaotang ji 白茅堂集.

![]()

Источники:

- Википедия

- Wikipedia

- Asian Research

- Hujian Chinese

![]()

Начало. 02. Основатели и учителя